By Litzey Anahi Ramos Landaverde

After a flight, bus ride, a couple of hours road trip in an overpacked old yellow Volkswagen Beetle, and a picturesque 1700-meter hike in 90-degree weather, I found myself in a fog-engulfed yet welcoming Nahua town in the mountains of Acaxochitlán, Hidalgo.

At first glance, the community of Santa Catarina, with a population of less than 500 inhabitants, felt largely familiar; a place and people deeply intrinsic to the diverse rural landscapes of Mexico. The smoke from a small forest fire, unmistakably emanating from scorched earth just meters above the furthest visible home, served as a strong juxtaposition to an otherwise charming town, somehow embodying the political nuances and attitudes I was yet to discover within Santa Catarina and surrounding communities.

As a visiting collaborator with PSYDEH, a local grassroots organization empowering rural and Indigenous women through training, tools, and mentorship, I had arrived to support the execution of their new civic participation program in the lead-up to the June elections in Mexico, Nosotras Decidimos, which the organization had launched in partnership with the National Electoral Institute (INE) within its four operating municipalities in Hidalgo. The program promotes rural and Indigenous women’s involvement in political processes before, during, and after the pending elections. Specifically in May, the focus was on recruitment and training for electoral observers in the lead-up to voting day. With limited knowledge of the bureaucratic procedures involved within Mexican national elections, but extensive exposure via my rural Mexican lineage to the rasping socioeconomic realities and inequalities experienced by everyday citizens due to historically deficient political representation, it’s safe to say I knew better than to have expectations.

However, that’s not to say I wasn’t also driven by plain curiosity. When a nation in the Global South with an extensive and deep-rooted history surrounding government corruption and election fraud makes international headlines for having two women as presidential frontrunners, all while maintaining a rising trend in gender-based violence over the past ten years (which sees ten femicides occur daily), naturally one becomes curious not only of covert political agendas but also as to the domestic reception of these social progressions ahead of election day.

Stories of Political Disillusionment

Answers started forming that first day in Santa Catarina when Josefina Guzman Rojas, program participant and member of the women-led Sihuame Tekikame cooperative incubated by PSYDEH over the last 2.5 years, shared with us a story about a local-level political candidate from a previous election cycle. Josefina shared that her hometown of Santa Catarina, the most isolated and rural town within their municipality, had gotten word that a candidate had scheduled a visit to their community and had promised gifts for the local children. She reported how mothers rushed to ready their children in their best and brightest, traditional trajes reserved for special occasions, awaiting what they hoped would be meaningful recognition from a potential representative. Josefina went on to share how, after hours of waiting, the candidate arrived with their team equipped with tons of professional cameras and gear, only to orchestrate photo ops with the children, give out single pieces of candy, and leave on their way without so much as a conversation with any potential constituent about their needs, demands, or concerns. The underlying passive tone with which she shared this example—one of many times members of this community have felt neglected, used, and shamelessly exploited for their Indigenous identity—struck me, especially as more women I spoke to shared the same downcast attitude.

In my conversations with women partners across the different cooperatives within PSYDEH’s network, it was clear that all of the women shared an overall distaste for political processes, a next to nonexistent faith in their leaders, and limited hope in change for the future. In areas where the largest movements towards sustainable development have been led by small community organizations and leaders who get little support or recognition, including initiatives for trash clean up and local history record keeping, there’s no question as to why faith is so dull. True political representation seemed to be a forgotten concept. Instead, plain acceptance that candidates would provide bald-faced lies, interior hostilities, and empty promises were all election cycles seemed to foster.

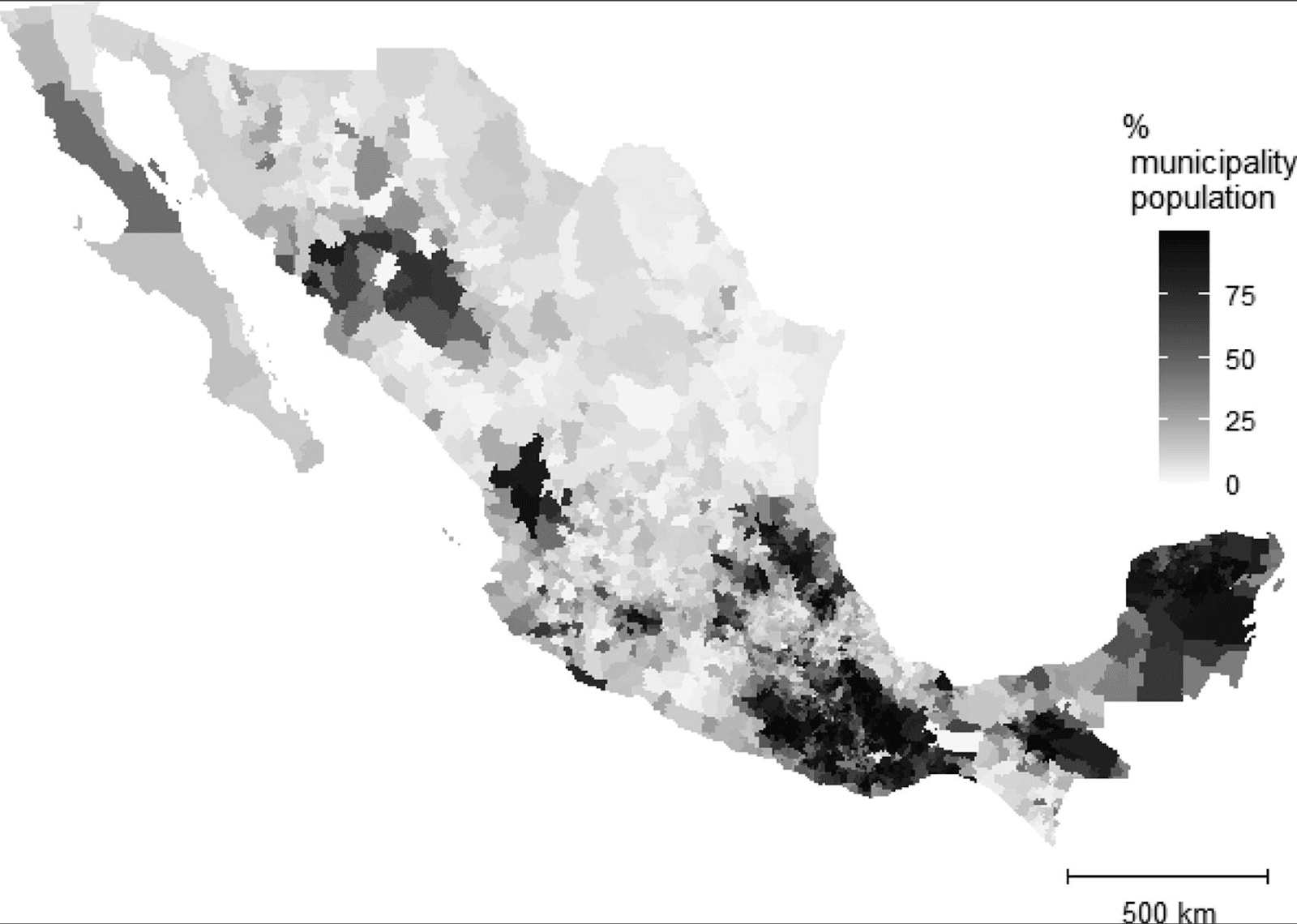

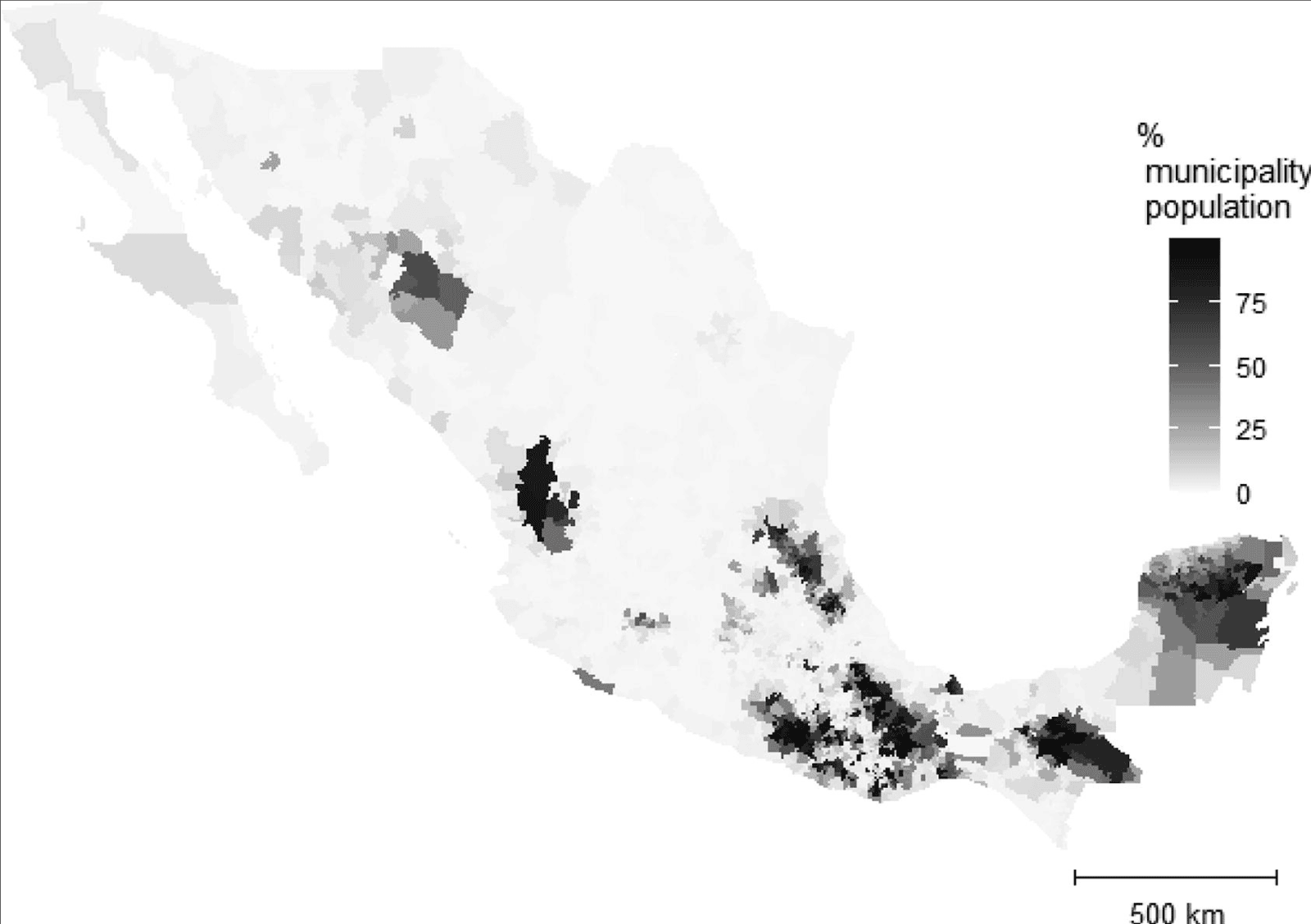

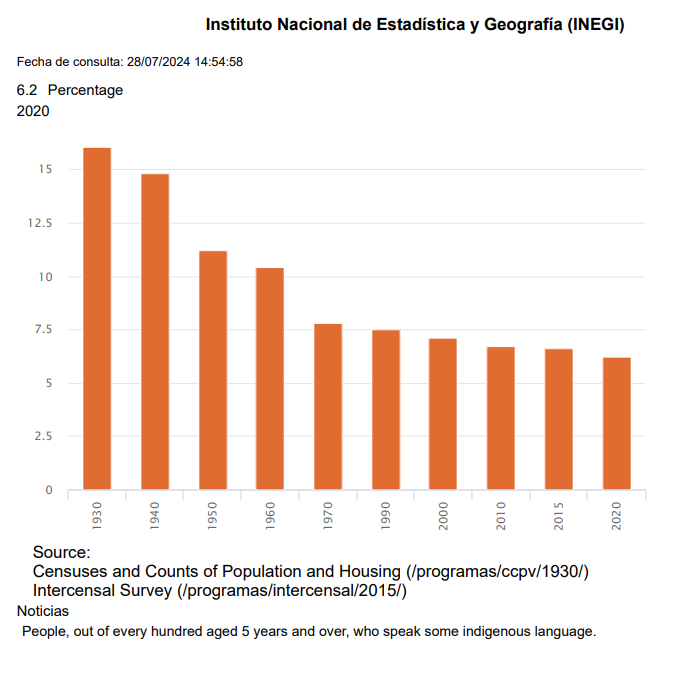

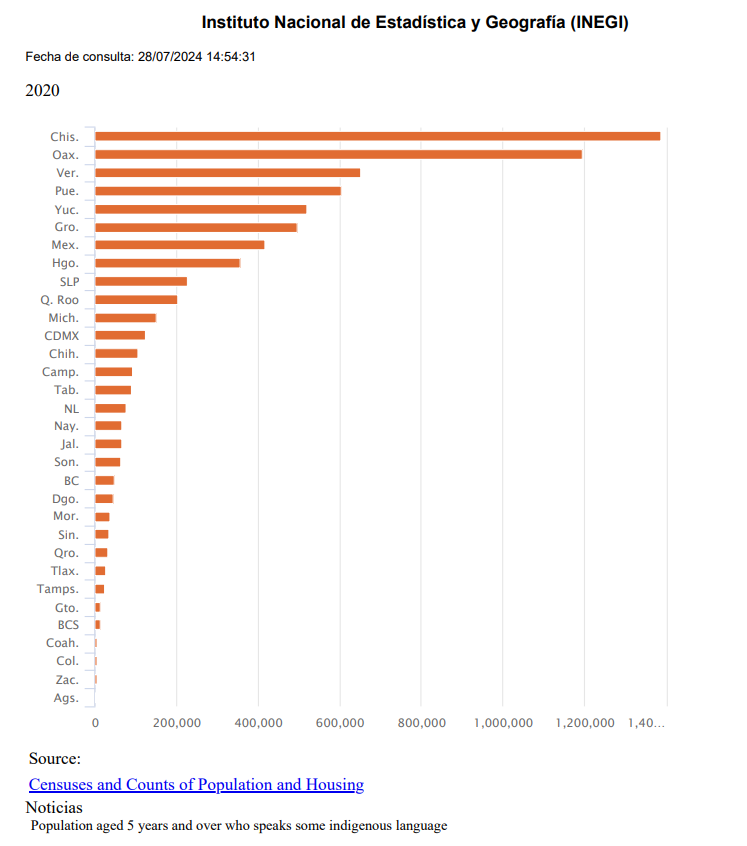

Historically in Mexico, there is ample evidence of a lack of consideration for the needs and demands of rural communities and the populations that largely make them up, particularly Indigenous peoples. Locally in the Sierra Otomí-Tepehua-Nahua region of Hidalgo, Mexico, the central issues that were brought up during interviews with PSYDEH’s women partners were inadequate public health resources and facilities, the deteriorating water distribution system in light of developing environmental changes, lackluster education and employment opportunities for youth, disproportionate aid, and the lack of government representatives and institutions to whom to address their concerns. Even something as physically threatening to a community as forest fires often go unreported because the population knows no government force will come to their aid. Instead, local brigades shoulder the emergency response, cost, and danger. The political reality in these communities often remains a posturing game; candidates show off photographs connecting with rural and Indigenous people then turn around and walk away. Political candidates run to represent people who are never included in the development of policies and proposals that will directly affect them.

Few sentiments expressed by women partners came as a complete shock considering that so many communities have been historically marginalized and largely failed by the Mexican state and its representatives. Beginning with the colonial era, followed by centuries of dispossession and displacement, and most recently the unique disparities faced by Indigenous communities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Their sentiments, deeply rooted in a legacy of marginalization, underscore the urgent need for systemic change and a reevaluation of how the state supports its most vulnerable populations.

Local Politics and Election Dynamics

On June 2, 2024, Mexican citizens voted for the federal president, cabinet deputies, local municipal president and deputies, and national senators. Adding to this dynamic election cycle was the vast participation recorded across all demographics with a 60% turnout rate making this one of the largest elections in Mexico’s history. This turnout also comes at a moment when more and more female candidates are appearing on ballots. Once incoming presidential candidate-elect Claudia Sheinbaum is sworn into office on October 1st, for example, the four highest seats within the Mexican government will be occupied by women: president, supreme court president, head of the National Electoral Institute, and the mayor of Mexico City.

This election season has proven historic for many reasons, some more tragic than others. As reported by Mexican consultancy group Integralia, candidate violence hit a modern record. There were 37 assassinations recorded leading up to Mexico’s elections, as well as 828 non-lethal attacks – an increase of 150% in political violence since 2021. This does not include threats and assaults against family members of candidates and candidates who withdrew from the election out of fear.

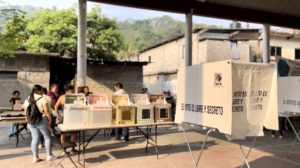

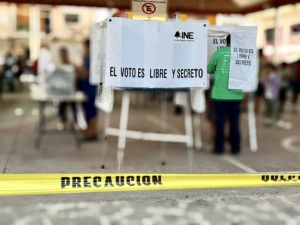

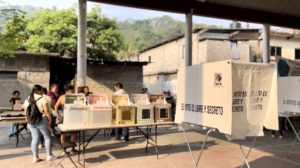

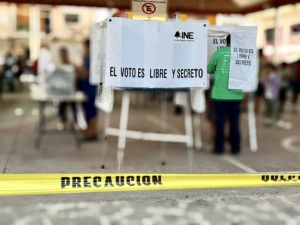

Fears over violent disturbances erupting on election day, as a result, also seemed legitimate. While rural Hidalgo is relatively peaceful compared to other areas of the country, the atmosphere was notably tense in some communities, especially in the municipality of Huehuetla where I joined PSYDEH’s women partners as electoral observers on June 2. Entering and exiting the rural and extremely isolated municipality deep in the Sierra Madre mountains became an entire security procedure as groups of locals armed with machetes and flashlights settled in at the main municipal entrances, personally inspecting passing vehicles with the voiced motive of protecting the election. These security efforts, I learned, were, allegedly, an attempt to keep party representatives and affiliates from arriving to disrupt the democratic process with illegal vote buying or other tactics.

Despite these organized security efforts, vote buying has long been a normalized part of election cycles in Mexico, especially rural Mexico, with citizens being offered anything from cash to groceries to bags of cement for their party loyalty. Speaking to first-time voter and electoral observer, Alison Vigueras Rios in Huehuetla, showed me that these fraud campaigns were still very prevalent in the community, particularly amongst young voters.

“[Many youths] still lack social consciousness and accept the instant gratification of quick cash in exchange for a single vote which many see as worthless anyway,” Alison shared. This vote-buying exchange is understandable if we consider we are talking about a community with extremely limited income opportunities. Alison’s recognition of a broken system while also stepping into an active role during the elections powerfully exemplified the commitment needed to foster effective democratic reform in challenging circumstances.

More Than A Vote

PSYDEH’s Nosotras Decidimos program was developed to address a lack of civic participation in rural and Indigenous communities in Hidalgo. During this year’s election cycle, the focus has been on empowering women beyond the vote to actively participate as electoral observers through an INE-formulated training program as well as a workshop series developed by PSYDEH supporting women to understand their rights as citizens, to research candidates to make more informed voting decisions, and to actively participate as local leaders before, during, and after the electoral process.

PSYDEH participants were not only formally educated on electoral processes, candidate agendas, and fraudulent voting practices, but also activated with local authority on election day as registered observers. In Indigenous communities where traditional gender norms are often heavily respected, the idea of women being actively involved in local government or public decision-making is still relatively uncommon until recently. Those I spoke to acknowledged this paradigm change for women is a massive step forward, especially when several of PSYDEH’s women partners were born before 1953, the year women gained the right to vote in Mexico. Somewhat shockingly, Mexican women are only celebrating the 70th anniversary of their full citizenship and rights.

In 2024, PSYDEH trained 32 electoral observers across five municipalities. Over 90% were women and most were first-time electoral observers. Salma Sinaí Soto Montes, PSYDEH’s Field Team Leader in San Bartolo Tutotepec, Hidalgo, explained that these electoral observers “must be citizens who are properly registered by INE and have undergone a course intending to exercise a citizen role within the electoral processes.” Observers, she described, “are precisely dedicated to observing that there are no actions that could come to harm the election process.”

Salma added, “Who better to have [as electoral observers] than women, Indigenous women—and men—who will be in charge of observing and verifying that this election cycle is done in a just way that does not harm any of the principles of human rights that we have as Mexicans?”

Another local woman in Huehuetla serving as an electoral observer, Rocio Rios Aparicio, shared with me that her experience in the PSYDEH-organized training was “very gratifying” because she “walked away with new knowledge, experiences, and friendships.” Rocio explained she was motivated to join the program to “create a change within my community because many times we have stayed quiet over very small or very big incidents that people never reported, so maybe participating will help make the process more democratic.”

Observing Election Day

On Sunday, June 2, Mexico’s Election Day, I noticed participating electoral observers resonated with Rocio’s words in their actions throughout the day. Observers and citizens alike were active, attentive, and committed to the role they were there to fulfill. Voters lined up in Huehuetla over a half hour before the ballot boxes were even scheduled to open at 7 AM, and many stayed the whole day, well after the polls closed at 6 PM until around 12:30 AM when the final results were posted. Many times throughout the day community members from behind the yellow security tape called over PSYDEH’s electoral observers to review and assess various incidents including suspicious activity concerning the presence of party representatives and suspected elder voting fraud. It was clear that the public respected these electoral observer peers for taking on their role and trusted them to fulfill their duties. Notably, this is not a type of public trust commonly awarded to many during local electoral processes.

I wasn’t the only one who noticed this positive reception of the electoral observers; the observers themselves recognized early on that they had stepped into a new and exciting level of local civic participation. Alison Vigueras Rios commented that it was “really surprising for me, at my young age, that I’m already participating in something very important for the change of my municipality.”

When asked how it felt to be seen in a leadership position by her fellow community members, Alison shared that she felt even more proud and accomplished to be acknowledged by her community for her role and was honored by their trust. I could see new levels of autonomy and empowerment unlocking in these women during this electoral process, but I also wondered how this empowerment might be sustained in the years to come.

Post-Election Concerns

Following all the exciting commotion of election day, everyone walked away with strikingly new experiences and perspectives on election cycles and their impact on communities. Recounting her personal experiences, Salma Sinaí Soto Montes shared, “I think it is all very important work. At least personally I will continue to disseminate and inform about the importance of electoral observations in citizen participation. Moreover, I think that something very important is how it breaks down so many prejudices held surrounding the vote counting.”

Similarly reflecting on the impact her involvement had on her community, PSYDEH Field Team Leader in Tenango de Doria, Jasmin Manrique Vigueras shared, “It was the first time I participated and I had no idea how it would be, but now that I have had this first experience, at some point if another woman wants to have the same responsibility that I had, then maybe I can give her some advice. Maybe the fact that I already have this experience and can share everything I observed will motivate other people to live [this experience], to learn how it is done, and to see the importance of observing the whole process.”

Reflecting on their election day experiences, all of the women I spoke to confessed that any disappointments had little to do with the candidates’ victories and everything to do with the hope that the winners would do one thing: keep their word and be true. Honesty and transparency in elected officials, again and again, were the paramount concern.

PSYDEH Field Team Leader in Acaxochitlán, Nancy De Lucio Vargas, shared that even if a local politician can’t keep their campaign promises, they should own that and be fully transparent with their constituents. She would appreciate that much more than lies. Nancy also shared that, for her, representation above all means, “transparency and truthful communication with the community and policy recommendations that take women’s voices into account” as they are the ones that “know their community, they know their neighbors, the schools, and the actual needs.”

PSYDEH Field Team Leader in Huehuetla, Citlali Aparicio Estrada, acknowledged, “What I would expect from this new government is that there should be direct communication as to what their plans are at a municipal level, including any and all social programs. We need clear information to give access to the people who need it most and inform people that these programs exist and consult people about their interest in participating, and that should not come from a place of imposition but rather a voluntary place, a consensual place.”

A clear consensus emerged from participants that their experiences as electoral observers promoted new levels of personal and collective empowerment, to ask new and pointed questions of their local government officials, and, potentially, to take charge in their communities and specifically demand more political accountability and meaningful change. This, many shared, could, potentially, be more probable now with a female head of state. Others remained hesitant.

The Road Ahead for Female Leadership

Overall, many have noted that this year’s elections in Mexico were monumental in shifting historical machismo paradigms. Salma reflected, for example, that any woman running for any office, local, state, or national now has the power of example– freshly elected officials promote a new “glass ceiling breaking” models for other women.

“Maybe in the future, my colleagues and I will be able to witness the political life of our community differently, not just in support of X color or X person, but the ability to decide and push things forward for our community,” shared Citlali Aparicio Estrada. Citlali continued sharing that she “would like to one day be a candidate”, and also “be part of a political process and see it from another perspective or a more on-the-ground perspective, working with real women and women who maybe don’t feel politically involved or represented.”

Collectively, it was clear that while more women in office is a good step towards gender equality and inclusion, political systems never come down to just one person. Aparicio Estrada even questioned whether women were being promoted as candidates just to fill a diversity quota and simply putting the face of a woman at the forefront of a party agenda.

This is where a demand for integrity and integration of local demands comes into play. Women shared a call for all candidates, regardless of gender, to carry out proper diagnostics to identify priorities, emphasizing local action and attention. Many voiced that positive local impact might be more possible with more women in office, as many consider women to have the capacity to lead from a more empathetic position and understand the needs of people more closely.

Following the election results, PSYDEH’s field team will continue through the rest of 2024 to advance the Nosotras Decidimos program. This includes a new workshop series to diagnose local needs and draft a citizen agenda to present by this fall as newly elected officials take office. Additionally, a short documentary film following PSYDEH’s electoral observers across different municipalities is in the works and set to be completed by September.

If there’s one thing I can confidently conclude from my experience observing the 2024 election with PSYDEH, it’s that the spirit of civic participation is alive and well in Hidalgo. While significant work is required for collective civic participation levels to reach political offices and create meaningful local impact, there is a new determination among PSYDEH’s team and women partners to understand and take on an active role in these once out-of-reach systems.

I am grateful for the kindness and openness with which PSYDEH’s team and their families received me during hectic times. They were not shy in sharing their recognition of flaws in the system and the active injustices and inequalities they face daily. It was evident to me that families in Hidalgo want their representatives to do good by the people. They want others to recognize the importance of civic participation to, in turn, reclaim both individual and collective power. These citizens hope to be represented, respected, and acknowledged by those in positions of power. They are willing to put in work to protect the integrity of democracy and demand that politicians do the same. If this spirit of civic participation grows and continues to be supported by more people, then real positive local impact may well be on the horizon.

Naeirika Neev

Naeirika Neev

What have you learned during your time with PSYDEH?

What have you learned during your time with PSYDEH?

In April 2023, I helped to lead PSYDEH’s first Google Lens workshops designed for four cooperatives based in the remote mountainous region of the Sierra Otomí-Tepehua-Nahua of Hidalgo. The workshop is based loosely on a curriculum and learnings from Viasat partners (see this promo

In April 2023, I helped to lead PSYDEH’s first Google Lens workshops designed for four cooperatives based in the remote mountainous region of the Sierra Otomí-Tepehua-Nahua of Hidalgo. The workshop is based loosely on a curriculum and learnings from Viasat partners (see this promo  The next day, the second workshop was held in Santa Catarina, a remote town in the municipality of Acaxochitlán. Santa Catarina is only reachable by an unpaved road. Here, the team faced the most barriers with our Google Lens workshop. With no wifi, the cooperative members, a majority who speak Nahua as their first language, needed to purchase extra data in order to fully take part in the workshop. Despite these barriers, participants seemed to be attentive and curious about these new accessibility tools. Many of the younger cooperatives members took a strong interest in Google Lens, seeing it as a tool to help better price the cooperative’s products, help with their children’s homework, and “show off to my husband” joked, Reina Cruz Rojas, president of the

The next day, the second workshop was held in Santa Catarina, a remote town in the municipality of Acaxochitlán. Santa Catarina is only reachable by an unpaved road. Here, the team faced the most barriers with our Google Lens workshop. With no wifi, the cooperative members, a majority who speak Nahua as their first language, needed to purchase extra data in order to fully take part in the workshop. Despite these barriers, participants seemed to be attentive and curious about these new accessibility tools. Many of the younger cooperatives members took a strong interest in Google Lens, seeing it as a tool to help better price the cooperative’s products, help with their children’s homework, and “show off to my husband” joked, Reina Cruz Rojas, president of the

The “right to connection” is more than having internet access; it includes the ability to connect with new communities and resources, empowering women to lead their own education and build independent networks. Marginalized communities can also represent themselves and tell their own stories using technology. Communities can gather their own data and implement responses to local social, economic, and gender inequalities. While it is understood that technology can exacerbate social issues, it can also strengthen solutions. For example, in the case of gender-based violence, women with access to technology are likely to have more tools and resources to help break patterns of violence.

The “right to connection” is more than having internet access; it includes the ability to connect with new communities and resources, empowering women to lead their own education and build independent networks. Marginalized communities can also represent themselves and tell their own stories using technology. Communities can gather their own data and implement responses to local social, economic, and gender inequalities. While it is understood that technology can exacerbate social issues, it can also strengthen solutions. For example, in the case of gender-based violence, women with access to technology are likely to have more tools and resources to help break patterns of violence.  In 2022, we took a giant leap forward in our work to make a sustainable impact in the fight against inequality in rural Mexico.

In 2022, we took a giant leap forward in our work to make a sustainable impact in the fight against inequality in rural Mexico.  ECONOMIC SOLIDARITY

ECONOMIC SOLIDARITY

DIGITAL INCLUSION

DIGITAL INCLUSION

When reflecting on 2022 work, a PSYDEH staff member says that “I think this is an important point for me…. to make an impact within our communities, prudent impact without impositions, that’s what we are doing.” Another staff member shares how she “is thrilled to see women graduating, believing in cooperative work and inspiring other women, to think that perhaps it was the persistence and workshops that made them believe that makes me proud.”

When reflecting on 2022 work, a PSYDEH staff member says that “I think this is an important point for me…. to make an impact within our communities, prudent impact without impositions, that’s what we are doing.” Another staff member shares how she “is thrilled to see women graduating, believing in cooperative work and inspiring other women, to think that perhaps it was the persistence and workshops that made them believe that makes me proud.”

The days are long and the work is hard for the PSYDEH field team members engaging our partner communities in rural Hidalgo, central Mexico. Six months into PSYDEH’s 3-year human-rights-oriented,

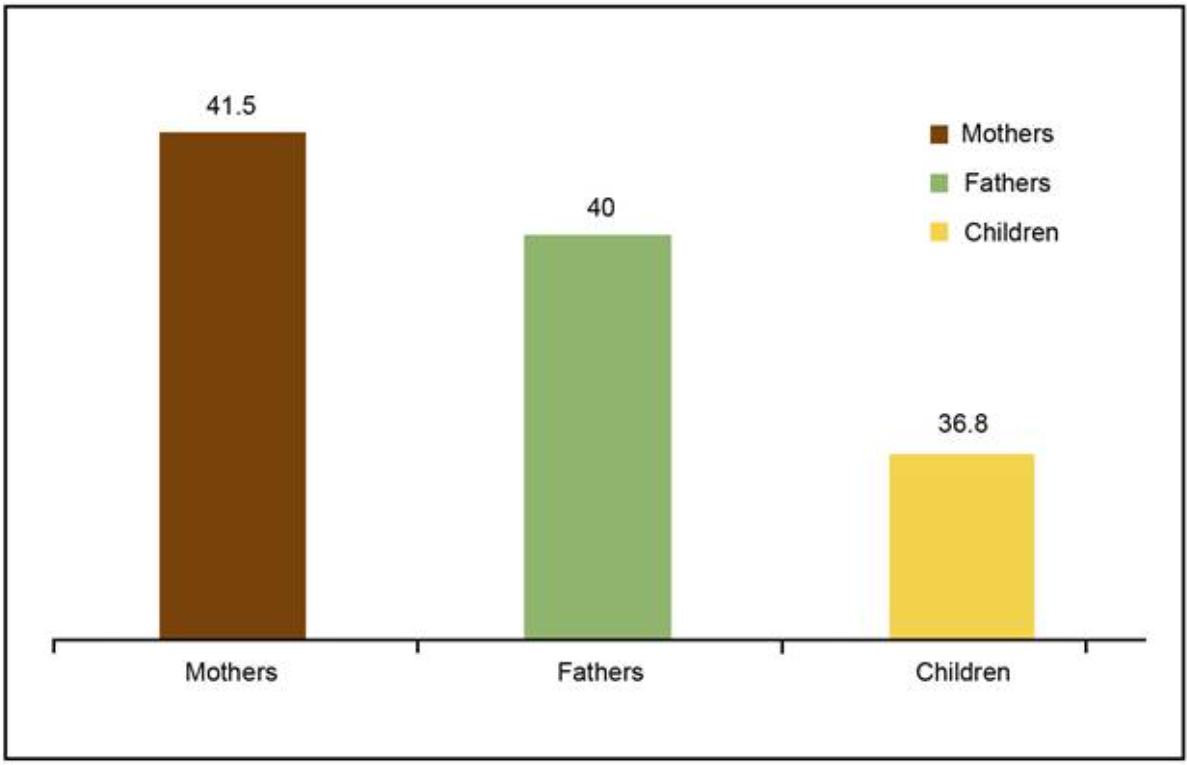

The days are long and the work is hard for the PSYDEH field team members engaging our partner communities in rural Hidalgo, central Mexico. Six months into PSYDEH’s 3-year human-rights-oriented,  In addition, team members must adapt workshop curricula to meet the unique needs of each woman and community, varying based on factors such as participants’ ages, Indigenous languages spoken, and literacy levels. For example,

In addition, team members must adapt workshop curricula to meet the unique needs of each woman and community, varying based on factors such as participants’ ages, Indigenous languages spoken, and literacy levels. For example,  Crucially, these are goals that are not so readily measured by conventional metrics. Although output metrics like the amount of money earned per woman per month, or the total number of workshop participants give us useful insights on short-term impact, they do not capture the full nuance of the long-term, sustainable human development we hope to achieve. For instance,

Crucially, these are goals that are not so readily measured by conventional metrics. Although output metrics like the amount of money earned per woman per month, or the total number of workshop participants give us useful insights on short-term impact, they do not capture the full nuance of the long-term, sustainable human development we hope to achieve. For instance, This is precisely why PSYDEH goes above and beyond when reporting to funders. Instead of simply providing obligatory output metric-oriented impact measurement assessments, we also encourage them to engage directly with our programs and to see for themselves the change they are creating. We invite external PSYDEH stakeholders to visit Hidalgo and catch our team in action. We have long-term collaborations with organizations and are transparent about our progress – for example, we have done over 20 update reports, such as

This is precisely why PSYDEH goes above and beyond when reporting to funders. Instead of simply providing obligatory output metric-oriented impact measurement assessments, we also encourage them to engage directly with our programs and to see for themselves the change they are creating. We invite external PSYDEH stakeholders to visit Hidalgo and catch our team in action. We have long-term collaborations with organizations and are transparent about our progress – for example, we have done over 20 update reports, such as