Thinking outside Tenangos: Alternative embroidery techniques from the Otomí-Tepehua-Nahua region in Hidalgo

Written by Arantza Caudillo

“What will happen when tenangos go out of style?” wondered Alejandra Ríos Perez, PSYDEH’s field coordinator. As people consistently indulge in overconsumption patterns to keep up with the latest fashion trends, it leaves PSYDEH’s team wondering: what will happen to the region’s economy when tenangos are no longer some of the trendiest pieces on the market? Many women from the Otomí-Tepehua-Nahua region of Hidalgo, Mexico rely on their beautiful tenango embroidery to support their families, sometimes as the sole household income.

In the last decade, tenangos faced a rapid increase in popularity. Many textiles were exported to the United States, Canada, France, Japan, the United Kingdom, Italy, and several other countries around the world. Tenangos even made an appearance in a popular US TV show “And Just Like That” in 2021!

With overconsumption patterns and trends that change faster than the seasons, PSYDEH’s partners and personnel worry that the popularity of tenangos will eventually fade. Still, the question remains: what can we do as consumers and as organizations to continue to support artisans from the Otomi-Tepehua-Nahua region? I propose to start educating ourselves and others on the region’s ancestral knowledge of embroidery techniques to expand the types of traditional textiles in the market and curb overconsumption patterns by spreading awareness about the detailed craftsmanship and cultural significance of each textile that enters the market.

With overconsumption patterns and trends that change faster than the seasons, PSYDEH’s partners and personnel worry that the popularity of tenangos will eventually fade. Still, the question remains: what can we do as consumers and as organizations to continue to support artisans from the Otomi-Tepehua-Nahua region? I propose to start educating ourselves and others on the region’s ancestral knowledge of embroidery techniques to expand the types of traditional textiles in the market and curb overconsumption patterns by spreading awareness about the detailed craftsmanship and cultural significance of each textile that enters the market.

The astonishing mountain range in the southeast of Hidalgo is home to three Indigenous ethnic groups: the Otomíes or Ñuhus, Tepehuas, and Nahuas. While most of those who belong to any of these groups adopted the more commercially successful “tenango” embroidery technique, many have vast knowledge of other culturally significant embroidery techniques that preceded the tenangos. These techniques include the punto de cruz otomi from the municipalities of Tenango de Doria and San Bartolo Tutotepec, pepenado tepehua from Huehuetla, and punto de cruz and telar de cintura nahua from Acaxochitlán. Thus, this article aims to delve into the history and cultural significance of each embroidery technique to inspire readers and consumers to explore handcrafts of the region beyond the tenangos and contribute to increased awareness around more sustainable, slow fashion.

From cave paintings to single mothers: The birth of tenangos

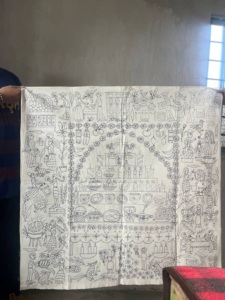

“This is the story las doñitas [diminutive for older women in Spanish] tell buyers,” explained Jaz, field corps leader for PSYDEH, after discussing one of the most famous stories about the birth of the tenangos. Jaz recounts that in the face of foreigners and potential buyers, many artisans share the same story about tenangos. The story follows a woman from the community of San Nicolas, belonging to the municipality of Tenango de Doria, who found inspiration in prehistoric cave paintings in “El Cirio,” and she began drawing those paintings onto raw canvas fabric, converting a new embroidery design into a culturally significant technique representing the Otomí cosmovision found in those paintings.

“This is the story las doñitas [diminutive for older women in Spanish] tell buyers,” explained Jaz, field corps leader for PSYDEH, after discussing one of the most famous stories about the birth of the tenangos. Jaz recounts that in the face of foreigners and potential buyers, many artisans share the same story about tenangos. The story follows a woman from the community of San Nicolas, belonging to the municipality of Tenango de Doria, who found inspiration in prehistoric cave paintings in “El Cirio,” and she began drawing those paintings onto raw canvas fabric, converting a new embroidery design into a culturally significant technique representing the Otomí cosmovision found in those paintings.

Tenangos emerged as an economic alternative for the region, and many ignored its true roots for decades (Vazquez y de los Santos 2015, 165). When asked about the meaning of the tenangos, many artisans will reply that the drawings are merely animals and plants they see “en el cerro” [on the hill] (Vazques y los Santos 2015, 163). However, the Otomí cosmovision lives deeply within each thread of the Tenangos. Over time, and with the support of Mexican academics, women from the communities of San Pablo and San Nicolas progressively gathered their memories to uncover the true origin of the tenangos.

The first ever tenango drawers were male curanderos [healers] during the 1960s who possessed ancestral knowledge to treat physical, emotional, and spiritual ailments (Vazques y los Santos 2015, 164). The curanderos used their knowledge of deities and plants to depict them in their drawings of tenangos, which the women would later embroider (Vazques y los Santos 2015, 164). Eventually, women also learned how to draw, and the activity became more feminized. While many forgot the curanderos’ role in making tenangos, women from the region have taken on excavating their own past to recover the true Otomí cosmovision behind tenangos.

The first ever tenango drawers were male curanderos [healers] during the 1960s who possessed ancestral knowledge to treat physical, emotional, and spiritual ailments (Vazques y los Santos 2015, 164). The curanderos used their knowledge of deities and plants to depict them in their drawings of tenangos, which the women would later embroider (Vazques y los Santos 2015, 164). Eventually, women also learned how to draw, and the activity became more feminized. While many forgot the curanderos’ role in making tenangos, women from the region have taken on excavating their own past to recover the true Otomí cosmovision behind tenangos.

Tenangos, as we know them today, emerged in a wider market in the 1960s as an alternative income for women whose family income did not cover the cost of living, for women who did not finish their education, for single mothers who could not leave their household, and for women seeking agency in a patriarchal economy. While these reasons dictate why tenangos exist, each stitch, thread, color, and drawing represents the Otomí cosmovision on both individual and communal levels.

What was before tenangos? Punto de cruz otomí from Tenango de Doria and San Bartolo Tutotepec

The Ñuhu people are the largest ethnic group in the Sierra Otomí-Tepehua-Nahua region with 20,113 self-ascribing as Ñuhu in 2020! Out of that number, 4,364 live in the municipality of Tenango de Doria, 5,037 in the municipality of San Bartolo Tutotepec, and 9,056 in Huehuetla (Martinez Patricio and Castillo Oropeza 2024, 9). If the tenangos emerged during the 1960s, what did the Otomí artisans do before them?

Embroidery and textile production represents an integral aspect of Otomí cosmovision, as these practices embodied the essence of the goddess Xochiquetzal. She not only represents love and sexual pleasure but also art. Many believed she protected artisans, especially those who embroidered (Vergara Hernandez 2023, 5). Thus, religious connections to embroidery show how this practice has endured within the Otomí people for centuries.

If you walk the streets of San Bartolo Tutotepec or happen to have the pleasure of being invited into an Otomí household, you will not miss the beautiful household items, specifically cloth napkins embroidered in punto de cruz. This stitch consists of sewing small X shapes following a previously drawn figure until the embroidery takes the desired look. Many Ñuhu women, especially older women, know how to embroider punto de cruz and usually own household items embroidered in this stitch. However, many of these items are purely for personal consumption and rarely reach the market.

If you walk the streets of San Bartolo Tutotepec or happen to have the pleasure of being invited into an Otomí household, you will not miss the beautiful household items, specifically cloth napkins embroidered in punto de cruz. This stitch consists of sewing small X shapes following a previously drawn figure until the embroidery takes the desired look. Many Ñuhu women, especially older women, know how to embroider punto de cruz and usually own household items embroidered in this stitch. However, many of these items are purely for personal consumption and rarely reach the market.

When asked why they abstain from selling these beautiful pieces, women often reply that they do not sell well compared to tenangos. Academics and consumers overlooked a significant practice of Ñuhu culture, as most focus on tenangos or other practices of the region and fail to produce academic research on punto de cruz. However, punto de cruz is just as integral and culturally relevant as any other technique.

While we lack academic information, many other Otomíes from other regions across Mexico have similar ancestral embroidery techniques that show the complexity and cultural importance of the stitch punto de cruz.

The Forgotten Embroidery: Pepenado and Telar de Cintura Tepehua from the municipality of Huehuetla

The Tepehuas make up a minority group in the southeast mountainous region of Hidalgo, concentrating the majority of their population in the municipal head of Huehuetla and in bordering communities (Martinez Patricio and Castillo Oropeza, 9). In a 2020 population census by the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI, for its acronym in Spanish), only 1,656 people self-described as Tepehua.

The pepenado and telar de cintura are central in Tepehua textile art. These types of embroidery techniques are found in shirts, skirts, corsets, and in poncho-shaped pieces called kexkemes, tapun, or quexquemitl made from two rectangular cloths sewn together to form a diamond shape with a central hole for the head. The embroidery in each of the pieces represents elements of Indigenous identity through the portrayal of Tepehua cosmovision regarding life and death and their relationship with the universe, stars, and nature (Flores Aparicio 2014, 127).

As demonstrated by Doña Juanita, artisan and treasurer of the cooperative Tierra de Bordadoras, the pepenado embroidery technique involves creating small, closely spaced stitches that form intricate patterns, often resembling dots or tiny loops. Pepenado typically requires fabric that allows the artisan to count each thread to make symmetrical stitches. The artisans place the embroidery on the shoulders, chest, and back of the shirt, as well as at the bottom of the skirt.

As demonstrated by Doña Juanita, artisan and treasurer of the cooperative Tierra de Bordadoras, the pepenado embroidery technique involves creating small, closely spaced stitches that form intricate patterns, often resembling dots or tiny loops. Pepenado typically requires fabric that allows the artisan to count each thread to make symmetrical stitches. The artisans place the embroidery on the shoulders, chest, and back of the shirt, as well as at the bottom of the skirt.

The motifs behind each pepenado include flowers, birds, mammals, and geometric figures. The design in the shirt’s sleeves represents the cycle of life and death and must be in the colors red, representing fertility; green, representing nature; or blue, representing life (Flores Aparicio 2014, 128). The pepenado embroidery represents the creativity of Tepehua women and shares their ancestral knowledge about human nature.

Moreover, Tepehua women elaborate the quexquemitl, commonly known as tapun in Huehuetla, with telar de cintura. The telar de cintura is a traditional weaving tool that tightens around the waist, and the other end ties to a tree. The action of weaving consists of perpendicularly intertwining two groups of threads–called urdimbre–in a parallel position along the fabric, which later interlock with crosswise threads called trama (Flores Aparicio 2014, 120). The tapun can be used as a cover over the head, a veil or shawl on the head, over the shoulders, or in a triangular shape over the chest and back.

The Tepehuas carried their cosmovisions, traditions, and knowledge in every piece they wore and every thread they embroidered and woven. The pepenado in shirts, skirts, and corsets and the telar de cintura in the tapun demonstrate the complexity of ancestral wisdom that continues to endure in today’s Tepehuan culture.

Telar de Cintura and Punto de Cruz in Acaxochitlán

Acaxochitlán, a municipality closer to the more urban Tulancingo, Hidalgo, is complete with stunning greenery, delicious gastronomy, and beautiful handicrafts embodying the people’s strong cultural roots. Unlike the Tepehuas, the Nahua people from Acaxochitlán have received national and international recognition for their intricate embroidered pieces, most importantly their quechquémitl– commonly spelled differently than in Huehuetla– and purses in telar de cintura and punto de cruz. However, these pieces have faced a similar fate as the Tepehua tapun, as they also experienced a limited market and clientele.

The municipality of Acaxochitlán borders with the state of Puebla and is one of the furthest out municipalities from the region yet much more accessible for urban trade. The Nahua people are the largest ethnic group in Acaxochitlan as 21,798 Nahua people reside in this municipality (INPI 2020). The communities of Santa Catarina and Santa Ana Tzacuala have notably received the most attention regarding their embroidered handicrafts.

Similarly to the Tepehua, the Nahua use the telar de cintura, a traditional weaving tool that consists of intertwining threads called urdimbre and trama, to elaborate the quechquémitl. Moreover, they also use colorful threads and punto de cruz stitch to embroider these pieces and inscribe their cosmovisions and ancestral knowledge. For instance, the floral tree in most of their quechquémitl aligns with their cosmological symbolisms (Báez Cubero 2020). Nahua artisans usually embroider flowers, animals, borders, and geometric figures on their quechquémitl in diverse colorways (Báez Cubero 2020). Nahua artisans did not limit themselves to quechquémitl and also embroidered napkins, bags, and folders using the same technique to sell them in local markets.

Similarly to the Tepehua, the Nahua use the telar de cintura, a traditional weaving tool that consists of intertwining threads called urdimbre and trama, to elaborate the quechquémitl. Moreover, they also use colorful threads and punto de cruz stitch to embroider these pieces and inscribe their cosmovisions and ancestral knowledge. For instance, the floral tree in most of their quechquémitl aligns with their cosmological symbolisms (Báez Cubero 2020). Nahua artisans usually embroider flowers, animals, borders, and geometric figures on their quechquémitl in diverse colorways (Báez Cubero 2020). Nahua artisans did not limit themselves to quechquémitl and also embroidered napkins, bags, and folders using the same technique to sell them in local markets.

The elaboration and use of quechquémitl using telar de cintura and punto de cruz represents Nahua ancestral knowledge that dates back to the prehispanic period. The quechquémitl carries a legacy of Nahua cosmovisions and culture, remaining an integral factor in preserving Indigenous traditions in the Otomi-Tepehua-Nahua region.

Conclusion

Curbing the narrative of fast fashion and design trends will allow us to discover alternative and sustainable pieces made to last a lifetime that also contribute to the development of the local economy. Sharing and purchasing pieces embroidered in tenango, punto de cruz, pepenado, and telar de cintura from the people of the Otomí-Tepehua-Nahua region will not only contribute to the well-being of artisans and their cooperatives, as well as the sustainable development of local communities, but also the conservation of important and long-standing cultures and traditions. Moreover, it is a small but impactful step towards a more holistic consumer market that values craftsmanship, artisans, and preserving cultural traditions, rather than a reckless, wasteful, and trend-saturated market.

As readers and consumers, I invite you to check out each of PSYDEH’s women-led artisan cooperatives–Cooperativa Tierra de Bordadoras,Yu Danxu Mpfei Di Töi, Ya Bombé Uedi Ko Nä Müi, and Cooperativa Sihuame Tekikame– to dive deeper into the Otomi-Tepehua-Nahua region handicrafts and support local artisans. I also invite you to browse the newly launched e-commerce platform “Sierra Madre Network” to explore and shop seasonal textiles from the aforementioned women-led cooperatives!

Cited sources

Vazquez y de los Santos, Elena. 2015. “El Arte Popular de las Mujeres de Tenango” in Mujeres, Feminismo y Arte Popular by Eli Bartra and Maria Guadalupe Huacuz Elias. Mexico: Universidad Autonoma Metropolitana

Martinez Patricio, Gustavo and Oscar Adan Castillo Oropeza. 2024. Ontologías ecopolíticas en la Sierra Oriental Hidalguense (México): una mirada sobre la ritualidad de los Ñuhu y Ma’alh’ama’ a la Sirena. Mexico: Revista Kawsaypacha.

Flores Aparicio, Palemon Alberto. 2014. Tepehuas de Huehuetla: Costumbres y Tradiciones. Hidalgo: Pacmyc.

Báez Cubero, Lourdes. 2020. Quechquémitl de Acaxochitlán. Museo Nacional de Antropología. https://mna.inah.gob.mx/detalle_pieza_mes.php?id=232

Instituto Nacional de los Pueblos Indígenas (INPI). 2020. Atlas de los pueblos indígenas de México. https://atlas.inpi.gob.mx/nahuas-de-hidalgo-estadisticas/

Vergara Hernandez, Arturo. 2023. “Los ÑHAÑHU u Otomí del Estado de Hidalgo, una Visión a Vuelo de Pájaro.” México: Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo.