Preserving Voices: Indigenous Languages of Mexico and The Worlds Within Them

The UNESCO Atlas of World’s Languages in Danger indicates that in 2024 there are 8,324 languages recorded worldwide, among which around 7,000 are still spoken today, and around 2,500 are in danger of disappearing. Mexico ranks fifth among countries with the most threatened languages. This article will explore the importance of Indigenous languages in Otomí-Tepehua-Nahua region of rural Hidalgo, their perseverance, as well as the efforts and challenges of preserving them.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis presents the idea that language influences, or even shapes, the way we think and perceive the world1. Through centuries of colonization and violent attempts to acclimatize Mexico’s Indigenous populations2, Indigenous languages remain a crucial tool in existence and resistance, a preservation of cultural identity, embodiment of history, and the world view or cosmovision of the people who speak them. Languages encapsulate unique cultural knowledge, practices, perspectives, and environmental interactions. Losing an Indigenous language would mean losing a very particular way of understanding the world and a gap in collective human knowledge.

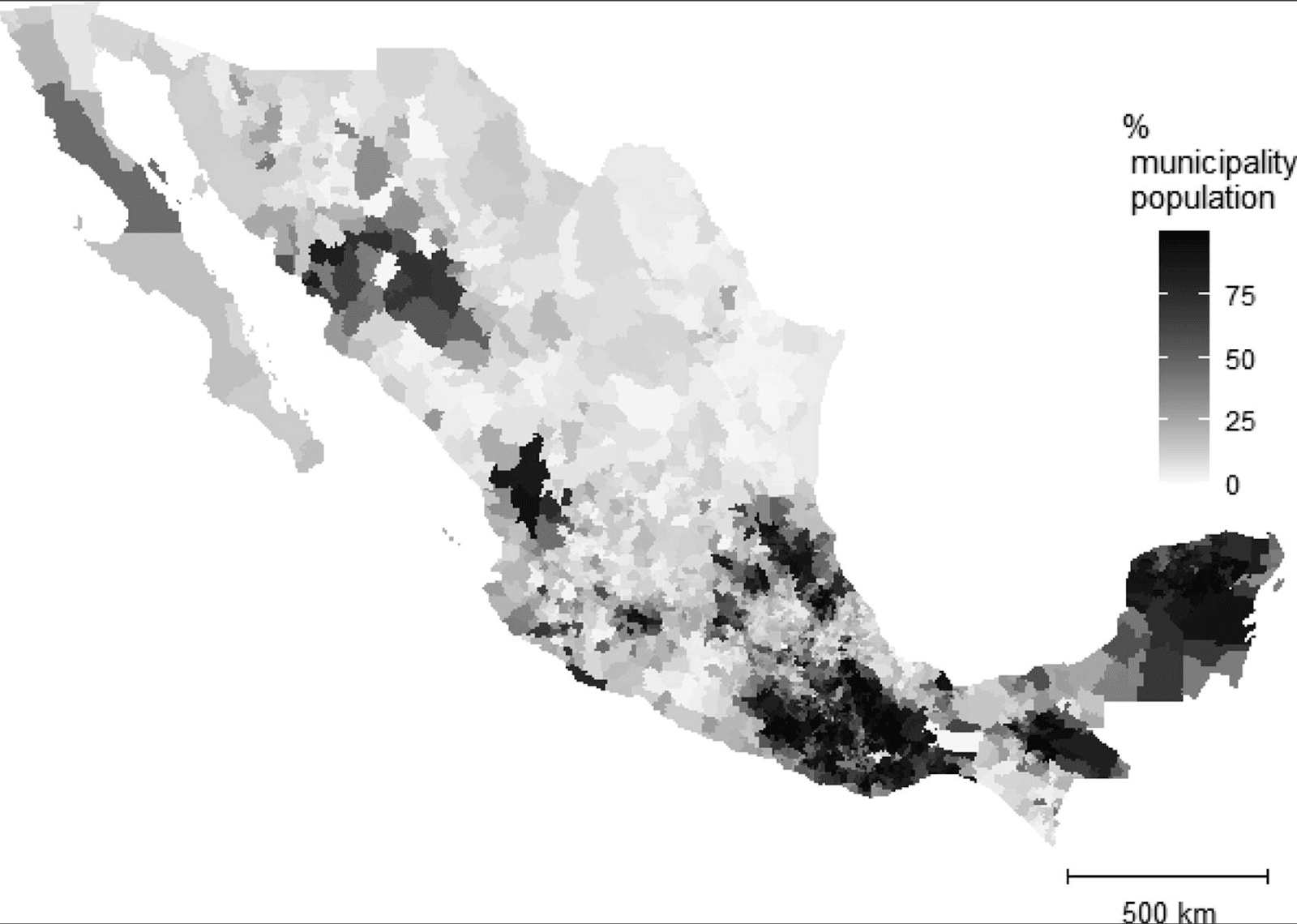

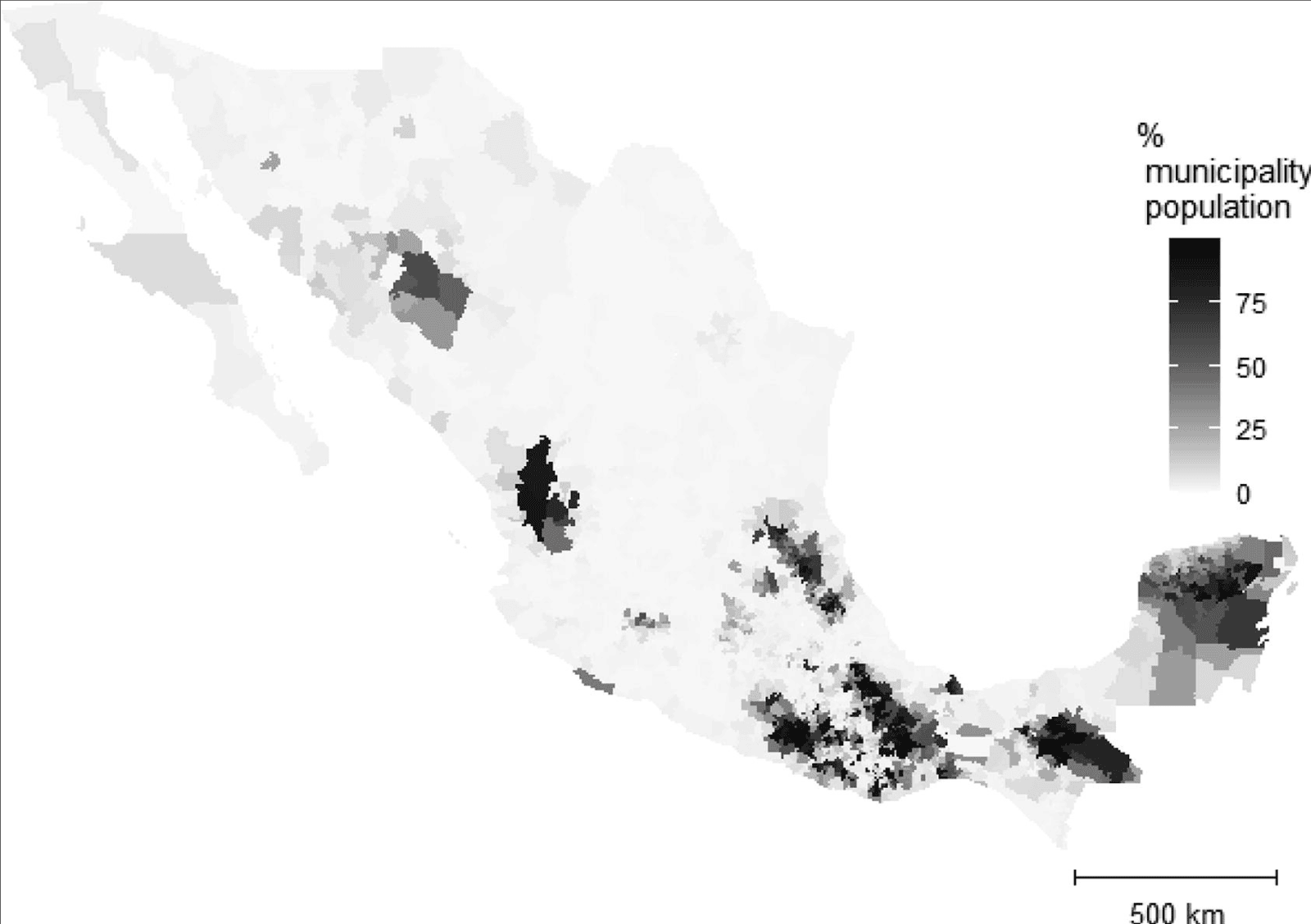

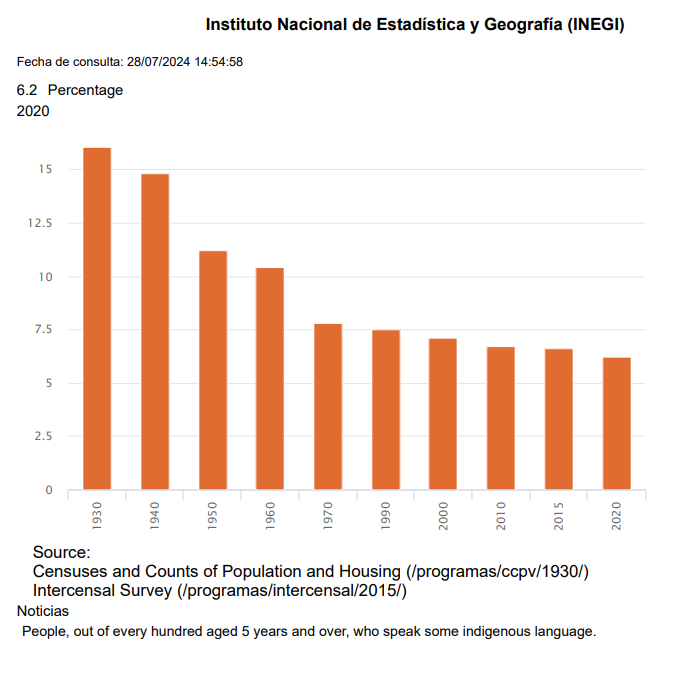

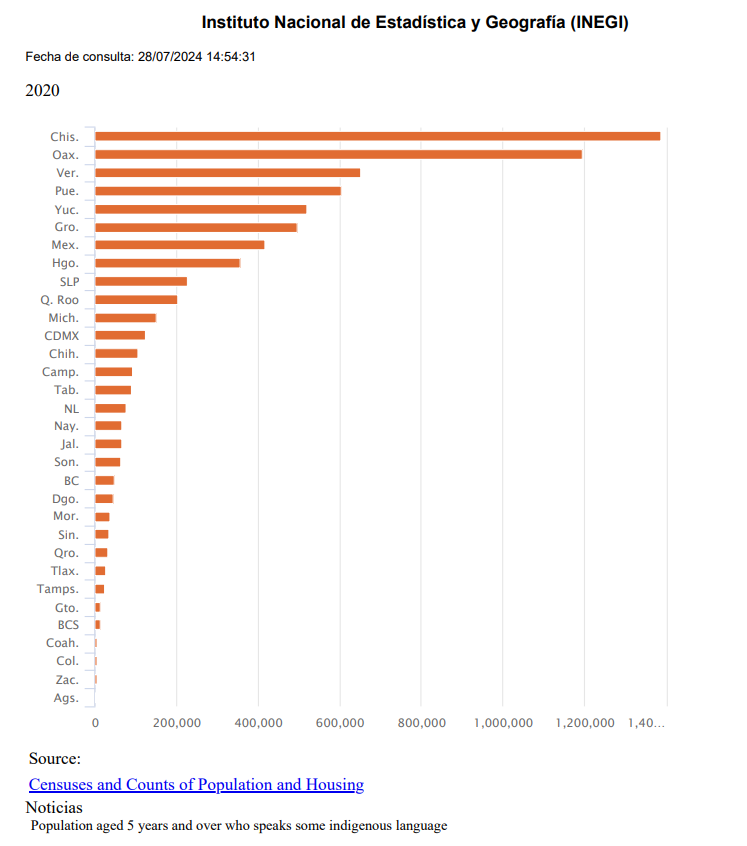

While a significant number of languages have been lost over time due to colonial-era policies pushing cultural homogenization3, as of 2020, there were 66 Mexican languages written and spoken in different parts of the country4. These language families stem from 11 independent language roots and were actively spoken by 7.36 million people in 20205. This means that while over 1 in 5 Mexicans identified as Indigenous, during the same period, only 1 in 20 spoke an Indigenous language, underlining the loss of these languages over time6.

Population share that ‘identifies’ as ‘Indigenous Mexican’, by municipality in 2015

Population share that ‘speaks’ an Indigenous Language, by municipality in 2015

In 1820, an estimated 60% of the population spoke an Indigenous language. In 1889 that percentage declined to 38% and then to 16% in 1930. In 2020, only about 5.8% of the population spoke an Indigenous language7. This decline can be largely attributed to official and unofficial institutional frameworks, as educational policies for Indigenous groups in Mexico from the late 19th century through much of the 20th century were used as a tool for cultural assimilation of Indigenous populations, partly by enforcing Spanish on the population and making the social and economic gain of learning the colonial language a necessity.89

Despite the influence of cultural assimilation, an emergence of institutionalized Indigenous organizations followed the Mexican Revolution (1910-1917), supporting gradual progress toward the recognition and preservation of Indigenous identity, culture, and ways of life. Public education, for example, once an institution of cultural erasure, forced assimilation, and colonial dominance, has only recently shifted to adopt a more multicultural and multilingual approach, even offering Indigenous language classes.1011

At this point, Indigenous languages are not just limited to learning in the household. Instead, institutional systems tasked to protect Indigenous cultures and languages have gradually evolved. In the 1990’s, Intercultural Bilingual Education (IBE) was introduced across the country to take a step toward cultural and linguistic inclusivity in the education system and recognize Mexico’s cultural diversity. In 2019, over 22,000 Indigenous schools had implemented IBE12. That said, these institutions continue to face limited public resources and policy support. As a result, culture and language preservation continues to fall on informal structures within households and society13.

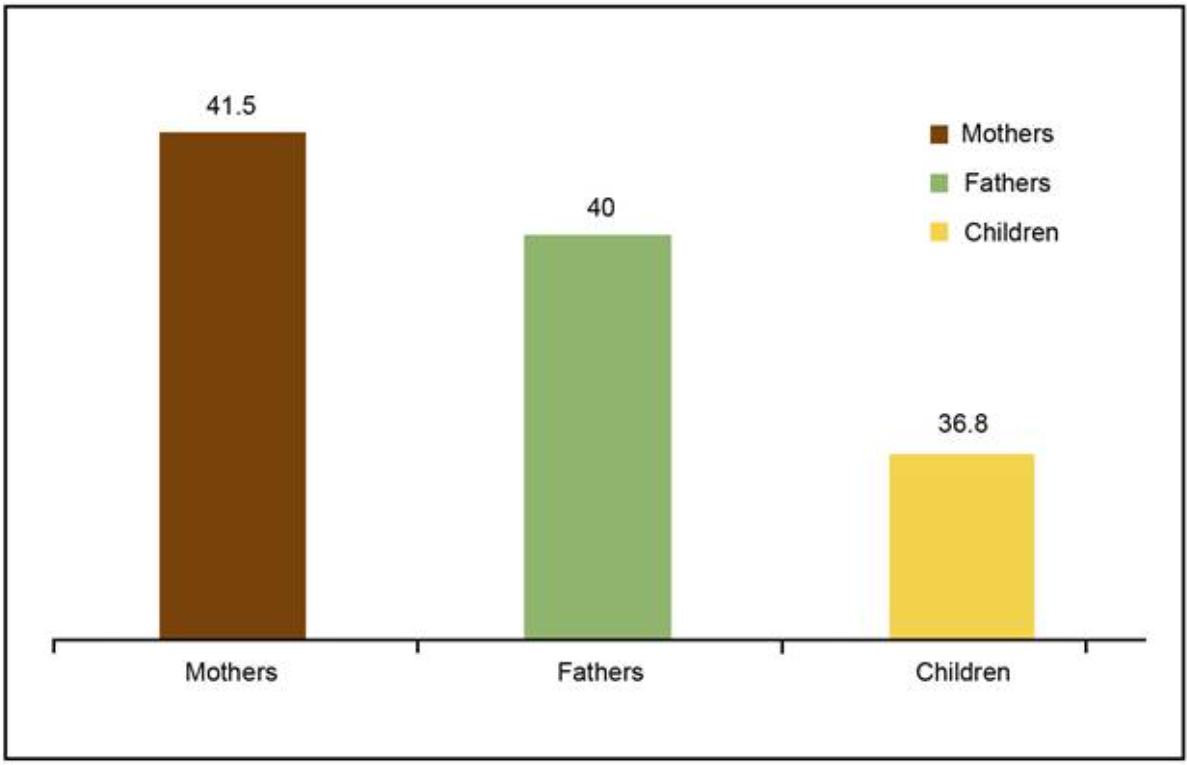

Comparison of rates of speaking an indigenous language among fathers, mothers, and children in indigenous schools in Baja California (percentages) 14

Keeping an Indigenous language alive is not only a form of resistance to colonial attempts at cultural erasure, it is also an act that allows for the preservation and revival of the vision of the world that is woven into that language, and thereby the continued evolution of that vision throughout time.

The Otomí Language

Otomí is an Indigenous language spoken by the Otomí people in central Mexico, primarily in the states of Hidalgo, México, Querétaro, Puebla, and Veracruz. It belongs to the Oto-Manguean language family, one of the largest and most diverse language families in Mesoamerica. Otomí uses the Latin alphabet for its written form, adapted by missionaries during the colonial period. Modern orthographies have been developed to standardize the writing of the language1516. The Otomí language is a crucial part of the Otomí people’s cultural identity and heritage, carrying the traditions, history, and worldviews of the community. Much of the Otomí cultural heritage is preserved through oral tradition, including stories, songs, and rituals that are passed down through generations17.

According to INEGI’s report, in 2020 there were approximately 356,950 speakers of Indigenous languages in Hidalgo, but the number of fluent speakers is declining, particularly among younger generations18. The Otomí language is considered endangered due to factors such as migration, urbanization, and the dominance of Spanish in education and media. There is often a lack of educational and linguistic resources available for teaching and learning Otomí, including a shortage of trained teachers and quality teaching materials. Economic pressures and the need for employment can lead to migration to urban areas where Spanish dominates, reducing the use of Otomí in daily life. Additionally, there can be social stigma associated with speaking Indigenous languages, which can discourage younger generations from learning and using Otomí19.

The Tepehua Language

Tepehua is another Indigenous language spoken in the Otomí-Tepehua-Nahua region of Hidalgo, specifically in the municipalities of Huehuetla and Tenango de Doria. According to recent reports, there are around 9,435 speakers of Tepehua today20. Similar to Indigenous people across Mexico, the Tepehua people have historically faced significant cultural assimilation pressures, making the preservation of the language a crucial aspect of the preservation of the culture. Despite unique features and a rich history, Tepehua is critically endangered, with a dwindling number of fluent speakers, most of whom form a part of older generations. Though there are some efforts to preserve and revitalize the language such as documentation and community-led classes, there are limited resources and a lack of institutional support, making this mission challenging21.

The Nahuatl Language

Nahuatl is one of the most widely spoken Indigenous languages in Mexico and has a significant presence in the Otomí-Tepehua-Nahuaregion of Hidalgo. It belongs to the Uto-Aztecan language family and even has several dialects, some of which may not be mutually intelligible. Nahuatl has a rich historical significance as the language of the Aztec Empire and continues to be spoken by Indigenous communities across Mexico. Despite its relatively larger number of speakers compared to Otomí and Tepehua, Nahuatl faces similar challenges of a dwindling number of speakers due to urbanization and a history of colonization and its ongoing legacy. Preservation efforts include bilingual education programs, some government support, and cultural efforts22.

Insight from Indigenous community members

In discussing the preservation of Indigenous languages, it’s vital to consider the lived experiences and insights of those who speak these languages. Jazz, a 27-year-old professional researcher at PSYDEH, a non-profit grassroots organization in rural Hidalgo, and a native of San Esteban who speaks the Hñähñu variant of Otomí, shared her perspective on the significance of the Otomí language to her community.

Jazz learned Otomí from her grandparents, as her mother, who worked in the coffee fields, left her in their care. She explained that her grandparents didn’t speak Spanish, so they always spoke to her in Otomí. This family-focused way of transmission highlights the role of older generations in preserving the language.

Jazz emphasized the deep cultural significance of the Otomí language, noting,

“It is a form of resistance, but it would also be a form of resistance not just to transmit it, but also to learn why it is important and to recognize the rights we have in the constitution to speak our language. Also not only to speak it, but to know exactly what it means. Because from the language comes identity, this relationship with the community, and how we participate as well. So, knowing all these aspects is important.”

She further elaborated, “It helps us a lot to communicate, express what we feel, create agreements, and even the meetings or assemblies in the community with local authorities are held in Otomí. Because most people speak Otomí. And really, the population that speaks it the most are the older people, around 50 years old and up.”

However, Jazz also noted the challenges faced by younger generations, particularly due to migration and the necessity of learning Spanish for economic opportunities. Many young people move away from the rural areas for better education and career opportunities, and have to adapt to living in bigger cities like Mexico City or Pachuca. She states that in these cases, learning Spanish is a necessity. She explained, “They change even the way they dress, the way they express themselves. The most important language now is Spanish, and many people also decide not to teach their children to speak Otomí.”

Jazz stated, “It’s very complicated to leave the community speaking only your native language and arrive in a super large city where businesses, schools, and people address you in Spanish. It’s very complicated to learn a different language from what we are familiar with.” This migration often leads to a language shift, with Spanish becoming more dominant among younger people, erasing Indigenous languages generation by generation. She further explained, “So, the same thing happens. The people who leave then stay in the city, have children, and obviously, the first language they have to teach them is Spanish.”

Jazz also spoke about the social pressures and discrimination faced by Indigenous language speakers. She recounted an incident at a bus terminal where individuals who couldn’t express themselves well in Spanish were told to wait for someone else to assist them. She reflected, “Sometimes we are treated as inferior because we come from a community, we are not natives of the city, and sometimes, not very often now, but it still happens that a person who speaks Otomí or another native language is seen as less than…”

Jazz highlighted the supportive role of organizations like PSYDEH in promoting Indigenous languages. She appreciated that PSYDEH does not impose Spanish as the sole language of communication but creates an inclusive space where people can express themselves freely in their native languages. She stated, “In the case of PSYDEH, we do not look for people who speak Spanish; instead, this invitation to participate in this network of cooperatives, in the workshops, is open to all people, whether they are Spanish speakers, Otomí speakers, Indigenous women, rural women—it is for all women.”

Jazz believes that the future preservation and revitalization of the Otomí language depend on early education and parental commitment. Despite obstacles there are individuals who are dedicated and passionate about preserving Indigenous languages, and deeply understand its significance in preserving and embracing Indigenous identity.

Insight from María Rosa Alicia Lozano Nery and Isidoro Hernández

María Rosa, a 56-year-old community member from San Pablo El Grande, also shares her perspectives on the current state of Indigenous languages and the challenges faced by her community in maintaining their cultural heritage.

Sra. Rosa highlights the generational shift in language proficiency in her family, revealing that though she does not speak any Indigenous languages, her grandparents did. She underscores the social stigma and neglect faced by Indigenous language speakers, explaining that, “sometimes Indigenous people aren’t attended to because they speak their language. They are pushed aside, and I think that shouldn’t be the case.”

Her husband, Isidoro, adds that “regarding the government, each government is different. Some value us, others don’t. We, as Indigenous people, sometimes get sidelined because we don’t know how to defend our rights.”

Sr. Hernández is not fluent in Otomí but can understand it well. Though he may be limited in his ability to use the language, he understands the impact of preserving it as it pertains to community and identity. He explains, “If I can’t speak it well, I can translate for the person who can speak it. In this case, I will help them. And if I can’t speak, that person will help me. Yes, it means that both of us are protected.” He further expresses, “The language… it shouldn’t be lost. It should continue. Mhm. The languages should continue.”

Conclusion

The preservation of Indigenous languages in Mexico is absolutely crucial, as the protection and preservation of Indigenous languages means the preservation of identity, culture, and unique world views associated with the language. While institutional frameworks have evolved to support the multicultural and multilingual realities of Mexico, significant gaps remain in public resources and policy support. The burden of language preservation has largely fallen on community members and informal structures, who attempt to pass on their heritage amidst economic pressures and social stigma. Insights from community members like Jazz Manrique Figueras and Doña Rosa underscore the intrinsic value of Indigenous languages to cultural identity and worldview. Preserving Indigenous languages is not only about maintaining linguistic diversity but also about safeguarding the cultural knowledge, practices, and perspectives these languages embody. As Mexico continues to navigate the complexities of its multicultural identity, Indigenous languages, and their speakers should be recognized as a valuable part of Mexico’s identity and future.

Author Bio

Naeirika Neev is a Master’s candidate in International Affairs at the UC San Diego School of Global Policy and Strategy, specializing in International Politics with a regional focus on Latin America. She holds a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science from the University of California, Berkeley. Naeirika has a diverse background in research and policy analysis, with experience conducting statistical analyses and engaging in sustainable development research in rural Mexico. She currently works as a Student Researcher at UC San Diego. Naeirika’s research interests include democracy, authoritarianism, and the role of women in liberation and democracy. She is particularly focused on how these themes intersect in different cultural and political contexts.

Naeirika Neev is a Master’s candidate in International Affairs at the UC San Diego School of Global Policy and Strategy, specializing in International Politics with a regional focus on Latin America. She holds a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science from the University of California, Berkeley. Naeirika has a diverse background in research and policy analysis, with experience conducting statistical analyses and engaging in sustainable development research in rural Mexico. She currently works as a Student Researcher at UC San Diego. Naeirika’s research interests include democracy, authoritarianism, and the role of women in liberation and democracy. She is particularly focused on how these themes intersect in different cultural and political contexts.

Connect with Naeirika on LinkedIn

References

- J.A. Lucy, in International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2001

- Farfán, José Antonio Flores. “Native Languages in Mexico. Challenges for the 21st century.” UNAM Internacional. Retrieved from [UNAM Internacional](https://revista.unaminternacional.unam.mx/native-languages-in-mexico-challenges-for-the-21st-century/).

- Velasco Ortiz, Laura, and Daniela Rentería. “Diversity and Interculturality: The Indigenous School in the Context of Migration.” Estudios Fronterizos, vol. 20, 2019, pp. 1-24. https://doi.org/10.21670/ref.1901022.

- Diego de la Fuente Stevens, Panu Pelkonen, “Economics of minority groups: Labour-market returns and transmission of Indigenous languages in Mexico”, World Development, Volume 162, 2023, 106096, ISSN 0305-750X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.106096 (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305750X22002868)

- Language classification from Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas (2008).

- Diego de la Fuente Stevens, Panu Pelkonen, “Economics of minority groups: Labour-market returns and transmission of Indigenous languages in Mexico”, World Development, Volume 162, 2023, 106096, ISSN 0305-750X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.106096 (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305750X22002868)

- Diego de la Fuente Stevens, Panu Pelkonen, “Economics of minority groups: Labour-market returns and transmission of Indigenous languages in Mexico”, World Development, Volume 162, 2023, 106096, ISSN 0305-750X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.106096 (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305750X22002868).

- Stavenhaven, 1988 Anuario de etnología y antropología social. Chapter 7: Los derechos humanos de los pueblos indios, Vol 1 (1988), pp. 130-136.

- Salmerón Castro, F. and Porras Delgado, R. (2010). Los Grandes Problemas de México. Part 4, Chapter 17,“La educación indígena: fundamentos teóricos y propuestas de política pública”. El Colegio de México, Vol VII, p. 509-546.

- Diego de la Fuente Stevens, Panu Pelkonen, “Economics of minority groups: Labour-market returns and transmission of Indigenous languages in Mexico”, World Development, Volume 162, 2023, 106096, ISSN 0305-750X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.106096.(https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305750X22002868)

- López, Luis Enrique, “Reaching the unreached: indigenous intercultural bilingual education in Latin America,” UNESCO 2010, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000186620

- SDG16+. (n.d.). Diversity and Inclusion in Indigenous Schools through Mexico’s Intercultural Bilingual Education Model. Retrieved from SDG16+ Policies

- Velasco Ortiz, Laura, and Daniela Rentería. “Diversity and Interculturality: The Indigenous School in the Context of Migration.” Estudios Fronterizos, vol. 20, 2019, pp. 1-24. https://doi.org/10.21670/ref.1901022.

- Velasco Ortiz, Laura, and Daniela Rentería. “Diversity and Interculturality: The Indigenous School in the Context of Migration.” Estudios Fronterizos, vol. 20, 2019, pp. 1-24. https://doi.org/10.21670/ref.1901022..

- Lastra, Yolanda (2006). Los Otomies – Su lengua y su historia (in Spanish). Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas, UNAM. ISBN 978-970-32-3388-5.

- “Otomí language.” Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Otomi-language

- Lastra, Yolanda (2006). Los Otomies – Su lengua y su historia (in Spanish). Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas, UNAM. ISBN 978-970-32-3388-5.

- INEGI. “Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020.” Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. https://www.inegi.org.mx/; Ethnologue: Languages of the World. “Otomi.” https://www.ethnologue.com/language/oto.

- Diego de la Fuente Stevens, Panu Pelkonen, “Economics of minority groups: Labour-market returns and transmission of Indigenous languages in Mexico,” World Development, Volume 162, 2023, 106096, ISSN 0305-750X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.106096 (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305750X22002868).

- Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas. “La situación de las lenguas indígenas en México.” Sistema de Información Cultural, Secretaría de Cultura. Accessed August 2, 2024. https://sic.gob.mx/ficha.php?table=inali_li&table_id=22.

- Hernández Montes, Maricela Tepehuas / Maricela Hernández Montes, Carlos Guadalupe Heiras Rodríguez — México : CDI : PNUD, 2004. 39 p. : retrs., tabs. (Pueblos indígenas del México contemporáneo) Incluye bibliografía ISBN 970-753-031-6

- Sullivan, Thelma D. Compendio de la gramática náhuatl. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas, 2014. 386 p. (Serie Cultura Náhuatl. Monografías, 18). ISBN 978-607-02-5459-8. PDF. Published online: May 30, 2014. Available at: http://www.historicas.unam.mx/publicaciones/publicadigital/libros/gramatica/cgnahuatl.html.